The tradition of Christmas Ghost Stories

The tradition of Christmas Ghost Stories

C.A. Asbrey

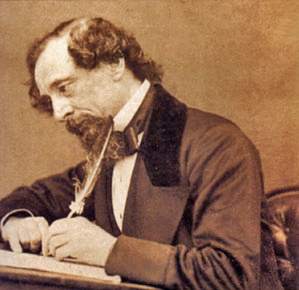

We are all familiar with Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, but how many of you know that it was written as part of a long tradition of telling ghost stories over the Christmas period? It goes back hundreds of years, and one which the Victorians enthusiastically embraced. Ghost stories are documented as part of the Christmas celebration as far back as Medieval times and beyond.

People instictively felt a need to gather together at the time of year when darkness crept up to those huddled around the warmth of the hearth. The old was on it’s way out, making way for the new. As the old year died, people remembered the past; the shades of the dead, and the impermanence marked by the passing of time. They didn’t just welcome in the light and decorations, they embraced the twilight and gloom too.

The Victorians loved to celebrate the dead. The very same people who spread the joy of Christmas trees, decorations, and celebrations, also loved to dress the holiday spirit up in retelling a more fundamental story of death and rebirth. At a time where people famously ‘made their own entertainment’, storytelling was an art form, and people could hold an audience spellbound by connecting mortaility to winter. They fed on the 19th century fascination with death and all things connected to it.

Just like the Yule log, Christmas tree, and evergreens, the ghost story was part of the older pagan tradition of Yule and the Winter Solstice. The shortest day of the year was seen as the point the departed had greatest access to the living. The generation who more or less invented the Christmas we have now, also enjoyed the whole cocktail of events and pastimes which became a rich cocktail of Christianity and paganism. Society itself impacted on the celebrations. A growing middle class had disposable income to spend on the holiday, and industrialisation meant that the winter downtime of an agrarian society no longer worked. Over the century the whole Twelve Days of Christmas became compressed into one big day as factories didn’t reduce their hours for the available light and ability to harvest. Robert Southey, writing in 1807, observed that “in large towns the population is continually shifting; a new settler neither continues the customs of his own province in a place where they would be strange, nor adopts those which he finds, because they are strange to him.”

By the time A Christmas Carol was published in 1863, the world of work had changed the season forever. The holiday was dropping in popularity, and for many people it was even a normal workday. If they were lucky, they had a special meal to go home to at the end of the day and a visit from family – and that was all. Cromwell had actually conducted a real war on Christmas, courtesy of puritanism, in the 17th century. The over-indulgence, singing,and drinking of previous generations was legally prohibited. Christmas Carols and special dishes of the season were even banned. While people had started celebrating again in the 18th century, it took the Victorian reinvention of the holiday to return the season fully to the public consiousness once more.

The publication of A Christmas Carol coincided with other commercial ventures, such as Christmas cards, publishing, commercial bakeries, and Christmas crackers. The Victorians loved to look backwards, cherry-picking the parts of the past which suited their nostalgic purposes. This historical sentamentalism was fed by older people telling grand tales of the extravagant Christmases of their youth, or of the extensive celebrations which lasted for almost two weeks being subsumed by the world of work. In short, the average middle class man had more disposable income than his grandfather, better housing, and more leisure time – but he didn’t have the grand holiday of days of yore. People started to feel they were missing out.

An increasingly technologically advanced publishing industry began to exploit the fact that people were prepared to spend more at Christmas. Until the 1840s spring had been the peak season of book production. October became the run-up to Christmas and became the peak season in the publishing calendar. It still is today. Bakers began to produce specialist cakes, pies and even breads, to tempt the consumer to part with a few hard-earned pennies. Christmas cakes, originally called twelfth cakes, began to rival wedding cakes in their extravagance for the rich.

While the well-to-do had always bought gift-books and keepsakes at Christmas, in the 1840s publishers were able to produce cheaper special Christmas reading material for the aspiring middle classes – Christmas supplements and special editions of serials and magazines.

The hearth was a symbol of family unity, and in many homes it was the sole fire. Only the wealthy could afford a fire in each room. In days before central heating it was the main source of warmth, so people were attracted to it like the proverbial moth. It was where families ate, kept warm, conversed, and entertained themselves with singing, parlour games, miming and acting. Reading aloud and story-telling were favourite occupations on cold winter evenings.

Dickens provides some insight as to what the Victorians read aloud in The Battle of Life (1846):

Grace, Marion and the doctor ‘sat by a cheerful fireside. Grace was working at her needle. Marion read aloud from a book before her. The doctor, in his dressing-gown and slippers, with his feet spread out upon the warm rug, leaned back in his easy-chair, and listened’.

Many of these books were ghost stories, but a new genre of fireside books appeared, such as Mrs Ellis’s Fireside Tales for the Young (1849), Elizabeth Sheppard’s Round the Fire Stories (1856), and William Martin’s Fireside Philosophy, or Home Science (1845).

There are many gothic ghost stories from the period worth a read. Elizabeth Gaskell’s, The Old Nurse’s story, was written for Charles Dickens’s magazine, Household Words, in 1852. The narrator – the old nurse of the title – is an old family retainer who has worked in the service of the same family for three generations. She tells the young children about a dark incident that she experienced in the company of the children’s mother, when she was a young woman and visiting her mother’s ancestral home Mysterious goings-on involving a spooky organ playing music and a scene reminiscent of Wuthering Heights.

‘An Account of Some Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street (1853). by Irish writer Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu was a master of the ghost story, and this creepy little tale is among his most popular. It takes a familiar trope of the ghost story – a couple of friends spend the night in an old mansion – and offers a sinister insight into one man’s past, a particularly nasty judge whose ghost visits the two men.

Charles Dickens didn’t keep his ghosts to A Christmas Carol . His masterful work, The Signal-Man, from 1866, features a protagionist who works on the railways. He observes that the mysterious appearance of a ghost always  precedes a terrible tragedy on the railway line.

precedes a terrible tragedy on the railway line.

Oscar Wilde’s, The Canterville Ghost‘,appeared in 1887. This charming tale isn’t scary, but it’s nice to have a bit of variation. It was the first of Wilde’s short stories to be published. An American family move into Canterville Chase and soon become acquainted with Sir Simon, ghost of the old owner of the manor centuries ago. But this is a ghost story with the Oscar Wilde treatment, so the family completely fail to be terrified by the presence of the ghost. Indeed, in a curious twist it is the ghostly Sir Simon who ends up terrified, when the twin sons of the American  owners produce a mock-up fake ghost. ‘The Canterville Ghost’ is a satire on the social and cultural differences between the American and English people, as well as on the Victorian ghost-story genre itself.

owners produce a mock-up fake ghost. ‘The Canterville Ghost’ is a satire on the social and cultural differences between the American and English people, as well as on the Victorian ghost-story genre itself.

Rudyard Kipling’s ,At the End of the Passage, was published in 1890. It’s set in India, about a British colonial official who – afflicted by the severe heat – begins to hallucinate and experience unsettling visions. But are they mere hallucinations? And can someone be so frightened of their own shadow as to – well, we’ll say no more, for fear of giving the game away. Kipling also wrote ‘The Phantom Rickshaw’ in 1888. The narrator has a torrid affair with the married Mrs. Wessington. Quickly his passion dies, his “fire of straw burnt itself out to a pitiful end,” and he tries to free himself of her. But even when he brutally tells her he can’t stand her, she refuses to believe they can’t live happily ever after. He makes plans to marry another woman, and Mrs. Wessington becomes so distraught that she dies, as Victorians who’ve been spurned are wont to do. Jack is very happy she’s dead. But he keeps seeing her private rickshaw around town. And then he sees her. Mrs. Wessington still has love left to give, whether Jack wants it or not.

M. R. James’, ‘Lost Hearts‘, from 1895. One of just two stories published in the Victorian era, many of his stories were written in the Edwardian period. This is an unsettling story about an orphan boy who goes to stay at the house of his distant relation, Mr Abney. Soon after his arrival, the young boy learns that two children who came to stay at the house in the past both mysteriously disappeared.

One of the very best, has to be Henry James’, The Turn of the Screw (1898). Written in 1898, this is the ‘ambiguous ghost story’ par excellence. The main narrative is told by a governess at a house who is put in charge of two children, Miles and Flora. The governess begins to see two figures of a man and a man around the grounds of the house, and learns from the housekeeper that Peter Quint and Miss Jessel, both former employees at the house (and both of whom have since died), were involved in a relationship and were also close to the two children. The sinister tale builds slowly, refusing to offer any clear solutions – which makes the whole business even spookier. More of a ‘novella’ than a short story (James himself liked the vague word ‘tale’), The Turn of the Screw is well worth devoting a few hours to on a cold autumnal evening.

Amelia B. Edwards, ‘Was it an Illusion?‘ This 1881 work, subtitled ‘A Parson’s Story’, is a ghostly tale which turns on the uncertainty surrounding the figures whom a school inspector spies on the road as he is travelling across the cold northern English landscape at dusk. Is he dreaming or hallucinating, or being haunted by ghosts? In many ways a classic of the genre, ‘Was it an Illusion?’ revels in the hinterland between rationalism and superstition which was so widespread in the late nineteenth century, which saw the founding of the Society for Psychical Research and the emergence of modern psychology and psychoanalysis.

Charlotte Riddell, ‘The Open Door‘ . This 1882 story shares much with the sensation novel, that bestselling genre of Victorian fiction that had enjoyed huge popularity during the 1860s and 1870s. Here we have another haunted great house, with a mysterious door that just won’t stay shut. Is it a ghost that keeps opening it? When the man investigating the strange case learns the dark truth that lies behind that door, it begins to look likely. What exactly went on behind that open door? Grab a blanket and a hot drink and start reading to find out.

Another ghost story shares the same title, and the same trope. ‘The Open Door’ by Mrs. Margaret Oliphant, was published in 1885 When the narrator’s young son begins raving about an unbearable noise he hears at night outside their Victorian country mansion, everyone thinks the boy is going mad. Except his father, who believes his boy is neither crazy nor lying. Lying in wait at night, he too hears the noise, the most soul-wrenching piteous crying he’s ever heard. It’s coming from the abandoned ruins of the old servant’s quarters. It isn’t easy to recruit friends and servants to track down the source of the horrible noise, but if he’s to save his son from “brain-fever,” he must uncover the secret of the abandoned cottage.

Robert Louis Stevenson, ‘The Body Snatcher‘. This 1884 Christmas ghost story, was advertised by six men who were paid to roam the streets of London wearing huge coffin-shaped sandwich boards and plaster skulls. These figures caused such a stir among the people of London that the police were called in to ‘suppress the nuisance’ Based on the body-snatching mania in Edinburgh during the early nineteenth century, where criminals would steal newly interred corpses from the local graveyards (and, where necessary, kill people to provide fresh corpses more quickly), Stevenson’s story turns on that very issue -the fact that body-snatchers often snatched the life out of their victims before snatching their bodies. But there’s a surprise twist in this story.

‘The Cold Hand,’ by Felix Octavius Carr Darley, is an 1846 tale where an overnight guest is tormented in his bed by the specter of, well, a cold hand, is the first story in a different sort of ghost story collection. The compilation of tales in this particular book Ghost Stories: Collected with a Particular View to Counteract the Vulgar Belief in Ghosts and Apparitions are intended to disprove the existence of ghosts. Its compiler, Mr. Darley, does so by presenting mystery stories for which the most exciting solution is “ghost,” but in actuality is something easily explained. These tales have less style than Sherlock Holmes stories, but the same idea of illuminating the impossible so that whatever remains must be the truth.

I hope you enjoy your holiday period, no matter what you celebrate. Ghost stories are notoriously hard to write, and I think the best merit highlighting in the present day. I love the tradition of Christmas ghost sories, and hope it’s something we can ressurect.

Sources

http://mentalfloss.com/article/59623/6-creepy-victorian-ghost-stories-read-right-now

10 Classic Victorian Ghost Stories Everyone Should Read

https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/how-victorians-invented-traditional-christmas-1881220

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-do-ghost-stories-go-christmas-180961547/

19th-century story illustration by FS Coburn. Photograph: British Library/Robana via Getty